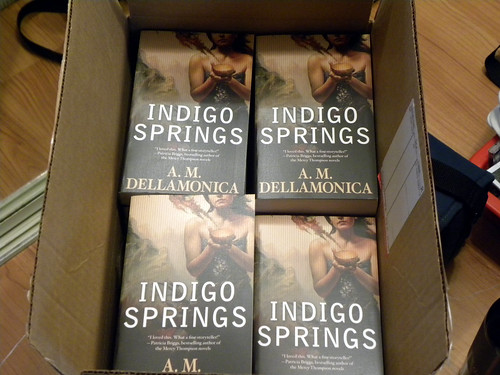

A couple links, first: my Quantum Leap rewatch of “A Single Drop of Rain” is up at TOR.COM, and there’s a new review of Indigo Springs here. Reviewer C.N. Rivera wasn’t crazy about the back and forth between the two storylines, and she hated Sahara from the git-go. To the latter, I confess I thought: “GOOD!”

Second, because she’s so darned interesting, I want to show you my friend Linda Carson, talking about art history and Lady Gaga’s references to same. (It’s a quickie: the Waterloo Ignite talks give speakers five minutes and twenty slides–the motto is “Enlighten Us, but Do it Quick.”)

I’m thinking “Bring on the meat dress!” may become a new catchphrase here at Chez Dua, which ties into some musings and observation of mine about language. None of us speaks quite the same language, you see: we all have our own DIY dialect.

Groups of people start building their own language as soon as they come together. Work groups, friendships, sports teams, theater companies, lovers… it’s part of the process of forging connections: in-jokes, the task-specific language, all this in-speak forms the true secret handshake. Once established, it can be used to refer back to specific facts, to memories, to emotions; it can also be used include or exclude. Your personal language is a merger of these separate variations, a fusion of the tongues of the family, the workplace, and your variety of social spheres.

The inspeak also can come with grammar and usage conventions. This spring I learned that in birding, the use of the term LBJ can refer to any one of the numberless brown handful-sized birds out there. LBJ stands for little brown job, and means, therefore, your basic bushtit or sparrowy bird. But I dug further, and discovered that within birding culture, you can’t just just go sticking this label on every LBJ that comes along. Once or twice, and you’re in the club. Once too many times, and you become some schmuck who can’t identify what’s in front of them.

(Also, if you’re me, this leads to an earworm of: LBJ, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today? Which sparrows appreciate not at all. Or it takes me to memories of the weird-butt animatronic LBJ cracking jokes at the Presidential Library in Austin. Really. Not joking.)

One very rich and heavily mined source of inspeak, of course, is pop culture. Here in North America, we eat, sleep, and breathe movies, TV, and books. We transform catchy quotes, imbue them with our own meanings, and sometimes make them impermeable to others in the process.

Some examples:

In my house, Monty Python has provided the line “S/he is a standard British Bird.” To us, this means any UK actor we recognize from multiple costume dramas, but don’t know by name. Not Dame Judy, not Rupert Graves… but the actress who was in Sense and Sensibility, say, who then played the King’s widow in Young Victoria. (I know, I could look her up, but that’s not the point.) Anyway, she’s an SBB.

Or the two blink and you miss ’em little boys on BlueBloods (What, you’re thinking, there are kids on Bluebloods?) have become Dr. Quinn and Medicine Woman thanks to Will Ferrell and Talladega Nights.

![]() Kelly and I crack up pretty much every time we say this.

Kelly and I crack up pretty much every time we say this.

Finally, no Child of the Eighties private language would be complete without a scattering of quotes, some mangled, from Ghostbusters. We were dragging ourselves out the door the other day and what came out of my mouth wasn’t “Rah rah, let’s go, we can do it, go team!” It was: “Let’s show this prehistoric bitch how we do things downtown.” It made sense. I’m not sure it should have.

This is a basic human behavior, but it can be a tricky thing to set up in fiction. If you’re writing something contemporary and you use actual pop culture, you may be stale-dating your stories. If you’re not, there’s a process. You make up the source, put it in context, use it appropriately… and bang! When you bring off that effect, of letting the reader in the club, of having them understand perfectly, on an emotional level, something that doesn’t make actual sense when scanned… it’s a powerful thing. It’s hard to do but it’s also something I find hugely compelling, when I encounter it as a reader.

Where do your linguistic quirks originate? If you’re a writer–have you ever pulled this off in a way you’re exceptionally proud of?