Lest you all think I am only interviewing veteran authors in this series, people well down the road and into their tenth, twelfth, and even twentieth novels, I’d like you to meet a fellow first time novelist: M.K. Hobson. Hobson and I have critiqued each other’s short stories, done readings together, and been an all-round mutual admiration society ever since Doug Lain (another writer whose first book should be out soon, incidentally) introduced us a few years back. She is witty, charming, a stunningly inventive writer, and great company. She ranks high on my personal list of Awesome People to Hang With.

Another random thing we have in common is that both of our novels feature dangerous mystical ooze!

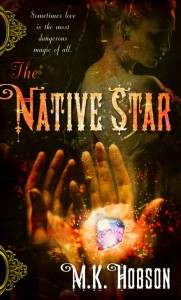

With an intro like that, how can you not want to know more? Here’s The Greenman Review write-up of her novel, The Native Star. Her website is here, or you can look for her at Orycon this coming November. Alternately, see what she has to say for herself right here!

I am a mom and a wife and a writer and a self-employed businessperson and a history buff and a dog owner and a nap enthusiast. How much of any one of those things I am varies greatly depending on the given moment.

The Native Star is my debut novel, and it’s due to hit the shelves on August 31. It’s a historical fantasy romance set in an 1876 America where magic is an accepted part of society. It follows the adventures of Emily Edwards, a spunky timber-camp witch from California, and Dreadnought Stanton, a snooty New York City warlock with a past. They’re thrown together on a desperate race across the United States—by horse, train, and biomechanical flying machine—to unlock the secrets of a magical artifact that could change the course of history.

I started writing fiction quite early—as soon as I could string words and sentences together, really. I’ve always loved to read, and as everyone knows, reading is the gateway drug to writing. The books that were formative to my experience were the Little House on the Prairie Books, the Nancy Drew mysteries, the Betsy-Tacy books by Maud Hart Lovelace, and all those horse books that Marguerite Henry wrote. I loved A Proud Taste for Scarlet and Miniver

by E.L. Koningsburg (it played a large part in the naming of my daughter Eleanor, actually.) In high school, I went through an anglophile phase in which I devoured Agatha Christie, Sherlock Holmes, Oscar Wilde and Saki. (During this period I used to re-read A Christmas Carol

religiously every December—it didn’t feel like Christmas unless I did.) Looking back on it now, I see that I resonated most strongly to books that took me back to an earlier era of history. I’ve always been fascinated by the way things used to be.

Instead of feeling humiliated or embarrassed, I felt a surge of joy. Someone thought that I could be a writer! That what I’d read sounded writerly! It was as if his comment gave me permission to think of myself as a writer (oh, high school) and after that moment, I did. “Writer” became part of my self-concept.

I’ve always integrated magical elements into my stories, because it made them more interesting. It gave me more to play with. It’s like, if you have a choice between the box of crayons with 16 colors or the box with 64 colors and the pencil sharpener built in—of course you want the bigger box! But I never thought of myself as a “genre” writer until I started trying to market my work. Then I realized that, in the eyes of the world, that’s what I was. (Of course, what exact “genre” I belong to remains to be seen, as my work scavanges tropes from most of them—romance, fantasy, thriller, historical, etc.)

Fiction writing has taken a back seat to other kinds of work these days, alas. With The Native Star coming out in August, and its sequel The Hidden Goddess coming out in May 2011, my focus has been on marketing. That takes a lot of time and creative energy. Three or four blog posts a day, tweets, giveaways, website maintenance, contacting reviewers, making up cool little cards and prizes and stuff … add that on top of a day job and family obligations and suddenly it’s past your bedtime and you still haven’t done a lick of fiction writing. Book promotion is a very insidious form of catwaxing, because it seems like you’re doing important work. But you’re not writing the next book. In any case, I’m not too worried about it. I do have about 30,000 words on a new novel that I’ll get back to once the crazy-time is over, and I have several more ideas in proposal stage that I’m excited to work on. I just relax and let it happen.

I committed myself to selling fiction shortly after my daughter was born in 1998. In the decade prior to that (the decade after I got out of college) I had been relying on Writer’s Market to find prospective markets. The problem with Writer’s Market was that it was only updated once a year, and the places you could be sure were still publishing (e.g., The New Yorker) weren’t going to have anything to do with you, while the smaller, more accessible markets might have already folded. I spent a lot of time sending stories into black holes. And in those days, when you wanted to query on a submission, it meant sending an actual letter, not shooting off a nice quick little email. People think it’s hard to break in today, but before the Internet it was way harder.

After my marriage and the birth of my daughter, I decided I needed to get some traction. There were starting to be some pretty good resources on the Internet. Using these, I found a writer’s group, then another. I found local writer friends who not only conviced me I had some talent, but helped me develop it. I adopted a new writing name, “M.K. Hobson.” My first pro sale in 2003 was—appropriately enough—to one of the premier online fiction markets of its day, Ellen Datlow’s SCI FICTION.

Writing meant giving up hobbies–even the idea of having hobbies. When people tell me they have hobbies, I stare at them blankly like they’re talking to me in Chinese. But I guess in some ways, writing is the ultimate hobby. It’s challenging, creative, and competitive. Would I like it if writing went from my avocation to my full-time vocation someday? Perhaps. But even if it never did, I’m still having fun.

The good surprises are, of course, the wonderful people I’ve met who share my passion for writing. It’s interesting, when I meet a person who is not a writer, I am often at a loss for what to talk to them about. What do people who are not writers talk about? I usually fall back on the Holy Trinity of chit-chat: kids, pets, and food.

The only bad surprise is one that is not unique to writing, one that life throws at you in innumerable circumstances: no matter what level of success you achieve, it will not be as great as you thought it was going to be. The success might be delicious, sweet, incredible … but at the end of the day, you’re still you, and the dishes still have to be done, and your toe still hurts from where you stubbed it, and the dog still has fleas. It really is about the journey, not about the destination—because you’re already at the destination. Who you are, and how comfortable you are with yourself, isn’t going to change based on a visit from the external validation fairy.

I’m entering a great time in my life, both personally and creatively. I’ve got a lot of hope and a lot of confidence. I’m looking forward to seeing what happens!

And a last word from Alyx: I’ve mentioned it before, but you really ought to check out The Native Star book trailer