Many years ago, when I first found myself giving people grades for their fiction projects, for the first time, I realized several things that may seem self-evident to you all…

–A huge part of being a writer is learning to turn a flawed draft into an utterly awesome work of fiction.

–The ability to revise a draft into something good develops with time and experience.

–Experienced editors can tell the difference between drafts with a lot of potential and those facing massive challenges.

–When we think we have nothing left to learn, we tend to stop learning.

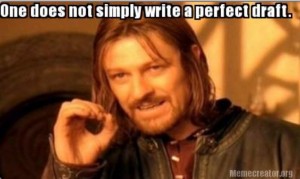

To be clear, I do not submit immaculate stories to workshop! When I am writing drafts, a high level of craft is at the bottom of my list of priorities. I’m a pantser at this stage in my life. I’m not above naming incidental characters things like CousinTwo, or even getting halfway through a paragraph and writing “Insert kick-ass detail here!” or “WTF does this house look like?”

The compulsion to get the story onto the page, to drag the character’s journey into the light, is my first and overwhelming imperative. By the time something of mine hits a workshop, I’ve had to go through it three to five times… and even then, it’s still pretty much a shambles.

So. Drafts are crap. Even more, we routinely tell people to write drafts that are crap! It’s so important to have something to revise that we urge writers to, you know, spew whatever they can onto the page in service of getting finished.

So this leads to an apparent contradiction, which is explaining to my students that I can look at their crap drafts and evaluate their commercial potential. To assert that I am qualified to say “This manuscript is this far along the road, while this one is further behind,” even though I will never see what their authors might accomplish in rewrite.

What makes the difference in such cases is the task list, the things the author needs to do to the story, and how tough those challenges might be. If the author of a given draft is writing vivid scenes that give the reader a sense of immediacy, if their characters are relatable and in conflict, if they’re more or less telling a whole story and that story has something fundamentally cool about it, they’re close. Closer, anyway, than a writer that hasn’t learned some of those basics, or whose line by line writing hasn’t yet begun to carry the reader smoothly through their story.

Does that mean I can look at ten drafts and say which writers will be successful? No. Almost anyone who writes ‘how to become a published author’ essays will inevitably will tell you that success in publishing often amounts more to being persistent than to any kind of innate talent.

The same person whose 2019 draft story suffers from insurmountable weaknesses might write a very workable story on their very next outing! They might then whip through an intriguing third project, and then dive into an experiment that almost succeeds wildly before it crashes and burns. Meanwhile, the person who seems to be halfway to publishable in the same workshop might stall out, or give up before they reach their next artistic breakthrough.

As editors and agents and teachers–as professional readers–we look at the pieces submitted to us and say “Yes, there’s a terrific story in here.” Or, alternately, “This one isn’t ready yet.”

I do sometimes get feedback from students that I shouldn’t be subjectively grading their stories at all. That they should get full marks for submitting them, without any evaluation. They’ll point out that many of their other instructors don’t give them any component of a grade that measures quality or merit, that indicates how well a given piece is doing. So it’s tempting to go that route… it’d save me argument and negotiation, and intellectual energy, and all sorts of work.

I get this, I do! In fact, the lion’s share of the grade in most of my courses is awarded just for showing up–doing the assigned work, writing the critiques, following the guidelines, submitting fiction on time. I give these grades because of the aforementioned persistence factor, but also to reward professional working practices. It is by and large the people who show up and do the work, after all–the ones who seem at first glance to merely be putting out quantity–who are building an artistic practice that will probably lead to sales.

Why hand someone back a story worth 10 points, then, with a 7 on it, and a note amounting to: This is 70% of the way to being salable in a professional market; for the things that are still in its way, see my workshop critique? It feels to the recipient much as a rejection does, after all, and rejections are painful.

(Spoiler: The answer is no. I don’t strive to have people practice feeling rejected.)

Most beginning writers, especially the serious ones, want desperately to know if they’re getting closer to publication, and what’s holding them back. When I speak at conventions, you can sense a hunger for that answer in the questions that come from the audience: How close am I? Will I get there? What do I do to get published? What does it take?

Some of what it takes is accepting, in your bones, that sometimes your stories need major rewriting.

Now that I’ve been at this awhile I have seen, time and again, that when I critique a story or exercise and attach a 100% grade to it, their authors take the problems I’ve identified within that work of fiction–and the need to address those problems–far less seriously than when they get that sobering 70%. It’s getting less than a perfect mark that brings people to my door or inbox with follow-up questions about how to embark on revision.

Universities require that students be graded. I can’t not do it. And for me, making those grades meaningful means awarding them in a way that brings writers more deeply into the revision process. If that also brings them back to my door with follow-ups questions and demands for resources, so much the better.