Category Archives: ucla-novel2

Journey with Marie Brennan

Marie Brennan is one of those people I know from the Internet, a writer I feel disposed to like well but, at the same time, someone whom I’ve never actually met in person. I first became aware of her because I’m a longtime fan of the SF Novelists blog, and her posts there on writing caught my eye. They’re accessible, smart, full of common-sense advice… and I constantly found myself sending the links to my students as optional readings. Check out this one, for example, on avoiding stereotypes with female characters.

Marie Brennan is one of those people I know from the Internet, a writer I feel disposed to like well but, at the same time, someone whom I’ve never actually met in person. I first became aware of her because I’m a longtime fan of the SF Novelists blog, and her posts there on writing caught my eye. They’re accessible, smart, full of common-sense advice… and I constantly found myself sending the links to my students as optional readings. Check out this one, for example, on avoiding stereotypes with female characters.

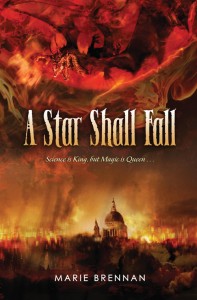

Marie’s novel A Star Shall Fall, whose prologue is online here,

has been waiting so patiently on my to-read pile as I’ve finished up the process of reading student submissions for my Novel Writing II class. That day is fast approaching, and I’m looking forward to it immensely. In the meantime, I asked Marie to tell us about her life and her writing journey . . .

I am a creature of sunshine and warmth; living in the Bay Area for the last two years, I’ve gotten plenty of the former but not quite enough of the latter. Until recently, I was in grad school in Indiana, studying anthropology and folklore, but my undergrad degree was in archaeology—all of which fits together pretty well for a fantasy writer. My current enterprise, the Onyx Court, I’ve nicknamed “my home Ph.D in English history;” it’s a series of historical fantasies set in London, one in each century from the Elizabethan period onward.

One of the oddities that crops up behind the scenes of a writer’s life is that when people say, “what’s your last book?” or “what’s your next book?,” your answer is frequently out of step with the reader’s perspective. To my eyes, the current project is the one I’m writing, which is the Victorian-era installment of the Onyx Court. I’ve almost got a finished draft of that, and will be turning it in to my editor by the end of the month—but readers won’t see that one until late 2011. Conversely, I’ve half-forgotten about A Star Shall Fall, which hit the shelves on August 31st and is what everybody else would think of as “current.” That’s the third book in the series, set in the eighteenth century.

Like many kids—especially those who grow up to be writers—I know I started telling stories at an early age. I grew up in Texas, and pretty much spent the entire summer in the swimming pool; I would splash around in the deep end, doing god knows what, with my brain wholly bound up in some nebulous plotless make-believe world. One summer a woman who babysat me and my brother and two other kids we were friends with taught us how to make books, binding paper into fabric and cardboard, and I wrote an utterly terrible mystery story in mine (something about a girl named Jessica whose cat was stolen). But I can point to a very precise moment when it all crystallized: I was nine or ten years old, and I’d just read Diana Wynne Jones’ novel Fire and Hemlock, which (among other things) is about a girl and her friend who collaboratively make up and write down stories about a hero and his assistant. I put that book down and thought, I want to tell a story.

I meant, by that, not just to live in the make-believe worlds inside my head, but to put them down on paper so that other people could share them. I went back to the computer (we were a technologically precocious family) and started typing up ideas about a quest for the Silversword, about which I remember nothing except I think the Silversword was actually a magical plant. In fifth grade I went to a writing workshop; in sixth I wrote a story that was way longer than the teacher wanted for a class assignment; somewhere around that same time I chose my pen name, because even at that age I knew my legal name (Neuenschwander) was far too unwieldy for commercial use. Throughout junior high and early high school I wrote stories that I would have called fanfiction if I’d known the term; they started off as me inserting my own characters into books I loved, and then once I figured out the logistical problems with that I began filing off the serial numbers and trying to make my own versions of them instead. (Which doesn’t work too well, by the way, unless what you start with bears only a passing connection to your source material anyway.)

The next sea-change came at the end of high school, when I came up with two ideas that were new. Not other people’s stories with some modifications; they were my own invention, and I could tell right away there was something different about them. They were stronger ideas, more mature. I began playing around with them in my usual way—which basically consisted of writing whatever scenes came into my head, not necessarily in any kind of connected order—and then went away to college, where I joined the SF association’s writing group, and that gave me external encouragement to produce words on a regular basis. Both of the ideas grew, until I had a largish chunk of one of them, more solid and connected than pretty much anything I’d done before. I asked the group what they thought of it, and one guy told me he liked it, but he thought the pacing was screwed-up and the characters were underdeveloped, etc.

I had one of those little brainwaves, where you look past the obvious problem to see the root cause beneath it: what I’d handed them wasn’t the beginning of the book! It was some piece out of the middle. No wonder it had those problems. So the summer after my freshman year, I sat down to write a beginning. I made a list of everything I needed to introduce or explain properly, and I came up with scenes to take care of that, and I kept going until I’d finished the list and joined my new beginning to the old piece.

And at that point, I had half a novel.

What’s more, I knew what came next, and I couldn’t wait to write it. So I had no excuse not to finish: I kept up the discipline I’d developed while putting together the beginning, writing every day, and in October of 1999, I finished my first novel.

Which isn’t Doppelganger, the first book I published (later republished as Warrior). No, that first book hasn’t sold, though it’s come so close, I want to tear my hair out. Unfortunately, it falls in this awkward crack right between YA and adult, neither fish nor fowl, and after having that book in my head for a decade and more, I just can’t re-imagine it to the extent necessary to make it be one or the other. But remember how I had two new ideas as the end of high school? Doppelganger was the other one. I wrote it in the summer of 2000, after revising and submitting the first book, and that was a pattern I kept up all through college.

By the time I graduated, I’d written five novels and had them all out in the world, making the rounds of publishers and agents. It was my way of coping with the stress and uncertainty of submission: if I had multiple books in play, all my eggs weren’t in one basket, and I had something to distract me from the months and months of waiting to hear back. (Seriously, there were occasions where an editor took so long to respond, I’d written an entire new book in the interim.) When Doppelganger had exhausted almost all of its options, with one incredibly near miss along the way, I took a long shot and sent it to Warner Aspect, where it sold in late 2004. If you want the full story on that, and what happened after, I’ve got a multi-part essay up on my site that tells all about my experiences with publishing my first novel.

From the age of ten, when I knew I wanted to be a published writer, I never had any doubt that I would make it. Which wasn’t just hubris, at least not once I grew up and learned how publishing works; so much of the game is a matter of persistence, and that’s something that was totally under my control. I could only lose if I quit, and I wasn’t going to quit, so. I was still over the moon when I finally broke through—after so many years of slamming my head against the wall, I couldn’t believe I’d actually made it!—but I never wanted to stop. If it happens that my career falters, my books don’t sell well enough and I can’t get a publisher to take me on, I’ll switch names and come back as somebody new. It’s been done before, by authors who did very well indeed the second time around. The only thing that really scares me is the possibility that publishing might collapse to such an extent that I can no longer make any kind of living at it. But even then, I won’t stop telling stories; you’ll probably find me in the thick of the crowdfunding efforts, trying to find a way to make deals directly with my fans, and publishing my novels online.

Barring that one mystery story I wrote in my cloth-and-cardboard book, and maybe something I wrote for class in second grade, my books have all been fantasy. I suppose a few of my short stories have verged over onto horror—certainly they’ve been published in horror magazines—but it’s always been speculative horror. The closest I’ve come to non-genre writing is the material I wrote for a puzzle hunt game played by Microsoft interns each summer; my brother used to be one of the game’s captains, and he hired me (like, with actual money) to write the story framework and vignettes that held the puzzles together. Those weren’t always speculative, though some of them were.

My plan, from about late high school onward, was that I would teach at a college level and write books in my spare time—a perfectly respectable path, followed by many writers before me. Most of those people, though, don’t try to start both things at the same time. I sold my first novel when I was barely two years into graduate school; it came out right when I finished my Ph.D. coursework. This falls into the odd category of “inconvenient success;” I would never say that I wish I’d had to wait longer to break in, but it messed up my academic plans more than a little, because now writing wasn’t a hobby, it was a job, and one that demanded a surprising amount of my time. I’d written novels while in school, but I’d never dealt with the necessity of copy-edits and page proofs and promotion and all the rest of the work that goes with being an author. Then I started writing the Onyx Court series, which is just about as research-intensive as academic work, and in the meantime writing was earning me more money than grad school (not that that’s hard), so when my husband’s company went bankrupt and he was out of a job, we decided it was time for a change of plans. We moved to California, he got a new job, and now I write full-time.

Which isn’t as shiny as my readers may think. I have to be very careful about my social life: my default state is not to have one. I sit at home all day, and see my husband at night, and that’s about it. So we take karate classes (at a dojo that includes my brother and his wife, who’s one of the teachers), and I run a role-playing game for some friends each week, and I do various other things to get myself out of the house, because if I don’t, my mood tanks something fierce. Like many writers, I’m an introvert, but that doesn’t mean unrelenting solitude is good for me.

I’m hoping to start writing YA alongside my adult fiction. Either way, I really want to get back to writing something in a secondary world—an invented setting, rather than historical or modern—I miss the scale of invention that you get to do when you’re making everything up. With my background in anthropology, I really enjoy putting together different societies, exploring ways of life that aren’t like what my readers are used to.

One of the pleasant surprises about publishing . . . do you know how you can tax-deduct business expenses? (In the U.S., anyway; I don’t know about other countries’ tax codes.) Well, research is a business expense. And depending on what you’re doing, “research” can be a very broad thing indeed.

When I set out to write Midnight Never Come, the first Onyx Court book, I decided that even though money was tight, I really did need to go to London. The city has changed a lot since the Elizabethan period, of course, but the streets in the City of London, the central part, are still almost identical to the medieval layout, and there were places I knew would be showing up in the book that I wanted to visit. Then, once I’d bought my flights, it occurred to me that I might as well try contacting the staff at those places, to see whether I might be able to meet with someone to ask questions, etc. So I sent out some e-mails, and got a variety of helpful responses back, and pretty soon I had a schedule for my week in London.

I didn’t realize what a fabulous scheme I’d inadvertently put together.

Take the Tower of London, for example, which shows up in the Prologue of the book. I went to the security gate and told them I had an appointment. They called up to the offices, and the woman came down to fetch me. They clipped a badge onto me and let me in—for free!—and then I proceeded to get a personalized, guided tour of the bits I’d come to see, up to and including being let into parts of the Tower that aren’t even open to the public. At Hampton Court Palace, my guide took me up onto the roof; at Hardwick Hall, I went onto the roof again, to see the “banqueting rooms” in the little towers, which again aren’t open to visitors. Throughout it all, I was in the company of people with a deep knowledge of their subjects and a wonderful eagerness to share what they knew . . .

. . . and at the end of it, I got to tax-deduct the entire trip.

There are definite downsides to writing as a career—low pay, job uncertainty, isolation, RSI—but man, it has its perks.

How it feels now is a weird combination of amazing and routine. On the one hand, selling a book to a publisher, seeing my work on the shelves—it’s this rare and magical thing that never stops being shiny. On the other hand, a lot of my friends now are writers, so selling books to publishers and so on doesn’t seem rare at all. Everybody does that, right? But you know, I get to spend my time making things up and being paid for it. This is, quite literally, my childhood make-believe turned into a legitimate career. How can that not be awesome?

Word Counts and Weather

I’ve typed in the pages from Tuesday’s THE RAIN GARDEN scribble session and got 780 words; Wednesday, meanwhile, got me to 1634. I hadn’t been sure how many words fit on the current notebook page, but it looks to be somewhere between 150-175. So six handwritten pages a day will get me my 900 words, it looks like.

I have a ripping busy work week ahead–my ten Novel II students have all turned in their finished fifty-page submissions. They’ve been very dedicated and I’d make them get up and applaud each other, if my classroom wasn’t virtual. Before I’d got to know this group, I couldn’t be sure how many of them I could expect to make it to this particular finish line. It is very gratifying to see how committed they are to becoming writers.

So–pile of grading, novel underway. Spinning hard and fast. Don’t be surprised if this space is a bit quiet this week. You know where to find me if you need me.

The prose glows when the heart flows?

Whether a piece of fiction ‘works,’ as we sometimes put it, depends both on the storytelling and on the line by line writing. In some ways, it’s problematic to view them as separate issues: if I decide a writer’s dialog lacks sophistication, for example, I might as easily talk to them about characterization as about their writing style. It all overlaps: I might find myself talking about why a story’s protagonist is so passive, for example, and then think, “Well, their behavior is caused by the rules of their setting… maybe I should address that.” And on we go.

Even so, it is often easier to try to talk about one story element at a time, and at least once in each of my Novel Writing workshops at UCLA, I shine the spotlight on prose. With that in mind, I had been trying, earlier this week, to come up with a sort of hierarchy to impose on the question. You know the kind of thing I mean: “Beginner,” at the bottom. “Professional Quality” in the middle. “Incandescent” at the top. With stages in between.

That proved beyond me, and I’m not sure it’s possible, but what I have done is think through a number of positive qualities that I look for in prose, things I think I might usefully employ to explain where a writer might focus their attention:

First, I kept Professional Quality: What this would mean, strictly in teaching terms, was that the line by line writing is smooth enough that were I an editor and if the piece in question worked as a story, I’d buy it. I think it’s important for a writer to know if they’re at or above this line.

(The rest are in no particular order).

Graceful: What I mean by graceful is that each event or action flows into the next, without there being a lot of clunky stage directions. Things like a whole pile of “S/he looked at him and said ___.” Glaring back at her, he replied, “____.” In a similar vein, grace would also mean characters move physically about the setting in an easy fashion. We don’t need to see them get up, get coffee, go to job if the story starts at job. The boring bits are gently shuffled offstage and we find ourselves comfortably entering each scene at an interesting moment.

Smooth: The general phrasing is good and the word choices have specificity. Strong verbs are chosen in place of adverbs, passive verb constructions, and said bookisms.

Clear: Simply put, I know what’s happening.

Sensual: Evokes the senses. I can imagine the scene; ideally, I feel like I’m there.

Sophisticated: For me, this means there’s starting to be some play with language, turns of phrase that at once capture ideas and images clearly and yet do it in surprising ways. The language illuminates things I’ve never considered before.

Maturity: This one feels as though it’s still a little dicey. It refers, essentially, to the emotional content of the story. I’m trying to get at the sense we get that the author understands that life is complicated, even when a particular character in his or her spotlight is maybe a bit simple-minded. I’m thinking about how it’s obvious Jane Austen doesn’t have the same good opinion of Mister Collins as she does of Elizabeth Bennett.

Transparent: By transparent, I mean nothing about the writing snags my attention, for good or ill: even if it might be low on beauty or style, it immerses me in the story; it doesn’t get in my way. I’m not noticing errors or clunky transitions. I’m just reading.

Grammatical: Either the piece is written in accordance with the rules of English grammar–not in a complete, perfect, uptight way, but in a way that doesn’t impact its transparency–or the author’s language is ungrammatical in a way that’s deliberate, appropriate and has some kind of consistency.

Balanced: There is a pleasantly readable mix of narrative, dialog, description, action. The prose isn’t all one thing.

Variable: The writer has slow and fast-paced passages. Their sentences are sometimes short and simple, sometimes long and complex. The characters don’t all speak identically. The writer can do a number of different things with relative ease.

Aesthetically pleasing : The writing in and of itself has some aesthetic impact. Obviously what one person considers beautiful may not resonate with another reader, but the sentences are put together in a powerful way–they sound good read aloud, they have strong rhythms. This is prose with the capacity to surprise, to bring a laugh, to provoke.

Confident: This one, again, seems hard to quantify. The writer can convey the setting or other information in a way that makes us believe it. They can tell us what their POV character is experiencing without always prefacing it with something like: “He saw.” If they leave a question dangling, it is done in a way that reassures readers this is intentional, and answers are coming, rather than a mistake. There’s no sense of hesitation or apology.

Streamlined: Here, I’m looking for a way to say “Not Wordy.” The need for explanation or repetition is minimized because there’s clarity–you know what’s happening the first time something’s said–and it makes sense. The flow carries the reader along, without wearing them out.

Individual: The writer is developing or has developed a voice that’s unique to them and their work. There are many who say you can’t teach voice. I don’t know if this is always true, but for the most part I prefer to stick to urging my students to get their prose up to that professional level and then build up more and more confidence. My hope is that someone who’s steadily improving on the above will in time start to take chances… and their voice will develop as they do so.

So here’s my question: assuming the above definitions were nice and clear, and maybe came with examples, how useful would it be to get a crit that said something like:

You are getting close to pro quality here, and there’s good balance between narrative, dialog, etc., but the areas where your writing isn’t transparent fall in the areas of grace and confidence. You have your characters eyeballing each other a lot, for example: you use “he scowled at X” to ensure we know who’s speaking to whom, and when you describe the Whoozification process, I can’t tell if that’s really how it works or if the character just thinks so.

About this post: I post writing-related advice and other information for students, fans and anyone who’s interested in the process of fiction-writing on my site. A few of you who enjoy these essays have, very kindly, asked if I have a donate button or something similar. I don’t, but you can always support my writing and teaching by buying books and stories, like this one.

Story Intro: “Five Good Things about Meghan Sheedy”

This story’s comparatively recent, which means I remember quite a few of the initial sparks for “Five Good Things about Meghan Sheedy” when I wrote it in 2004.

First, I was developing the (loosely) standardized critique style that I now I use for most of my UCLA Extension Writers’ Program classes. I had settled on a ‘rule’ for myself that no matter where a student was at, craftwise, I would find at least five positive things to say about every story submitted for workshop. Five things. It’s arbitrary, I know, but it ensures that everyone gets a comparable amount of encouraging feedback, and that I’ve identified a few good things they can build on. When your students never see you face to face, when you’re just keystrokes on teh Internets, the being positive up front component of critique is even more important than when you’re in the room together.

As teaching discipline, it has worked out well, and I still do it with Creating Universes, Building Worlds, Writing the Fantastic, and most other classes. (Novel Writing II has been a different kettle of fish.)

So… five good things. The fact that it was a fixed number snagged on something in my writerbrain. It occurred to me that there could be aliens with whom something like this was an actual custom. A lot of cultural things are arbitrary in some way or another; the answer to “Why?” is often “That’s just how we do it.”

Another second component of the story was Meghan’s temper. I’d had the opportunity to closely observe someone who was going through some really difficult things, and went through a stage of dealing with it by biting off the heads of everyone within hearing range. I’m more of a conflict avoider, so it was on my mind.

As for how this evolved into a squid story… well. I had been reading a good deal about the U.S. military intervention in Vietnam in the Sixties, and thinking about proxy wars, and how it might look if two offworld powers started kicking Earth around in some fashion. I thought of setting it in the same universe as the Slow Invasion stories, further on down the timeline, but that Earth has a dense offworlder population that considers our mudball home, and those individuals wouldn’t go anywhere just because a war busted out, and I didn’t want them added into this particular stew. They didn’t quite fit. So, despite the fact that the two universes have similarities (offworlders who are far more advanced than us, exploiting their supremacy) I decided they couldn’t be lumped together.

Later, as I wrote more squid stories, especially the ones about Ruthless, it became apparent to me that “Meghan Sheedy” probably takes place late in the Proxy War–the U.S. is the last country of any significance to fall to the Fiends, who work their way from the Mexican border to Canada. (We fold like the paper kitten we are, maybe five minutes after they get here. Ten if they stop for coffee.) Since this story takes place in Seattle and Seattle’s near the border, the geography makes that much apparent. But those were decisions I made later; in the meantime, I was imagining the Seattle I know, the familiar skyline pocked with Dust craters while ordinary twenty-first century peeps tried to cope with bombing and the destruction of their way of life, with occupation and collaborators and the danger of constant surveillance by both sides.