Caitlin Sweet is the author of three adult fantasy novels: A Telling of Stars (Penguin Canada, 2003), The Silences of Home (Penguin Canada, 2005), and The Pattern Scars

Caitlin Sweet is the author of three adult fantasy novels: A Telling of Stars (Penguin Canada, 2003), The Silences of Home (Penguin Canada, 2005), and The Pattern Scars (Chizine Publications, 2011). The Door in the Mountain

(Chizine Publications, 2011). The Door in the Mountain (Chizine Publications, 2014) is her first young adult book, and it is on the shortlist for this year’s Sunburst Award, whose jury says:

(Chizine Publications, 2014) is her first young adult book, and it is on the shortlist for this year’s Sunburst Award, whose jury says:

Sweet has fashioned a gorgeously dangerous world ruled by equal parts beauty, magic, violence, and the whims of gods.

The sequel, The Flame in the Maze , will be published in fall 2015. Her first three books were nominated for Locus Best First Novel, Aurora, and Sunburst Awards; The Pattern Scars

, will be published in fall 2015. Her first three books were nominated for Locus Best First Novel, Aurora, and Sunburst Awards; The Pattern Scars won the CBC Bookie Award in the Science Fiction, Fantasy or Speculative Fiction category.

won the CBC Bookie Award in the Science Fiction, Fantasy or Speculative Fiction category.

I asked, first:

Is there a literary heroine on whom you imprinted as a child? A first love, a person you wanted to become as an adult, a heroic girl or woman you pretended to be on the playground at recess? Who was she?

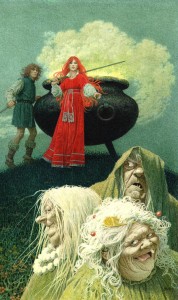

Eilonwy, daughter of Angharad—the high-spirited princess of the House of Llyr, who tossed her red-gold hair all the way through the five books of Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles.

Can you remember what it was she did or what qualities she had that captured your affections and your imagination so strongly?

I was seven when I first encountered Eilonwy. At the time I believed I might, in fact, be a princess from another world who’d been dropped off on this one, and left here far longer than intended, due to some cataclysm or other. Eilonwy was the princess I yearned to be. I knew it the moment I heard her voice and saw that red-gold hair: she was young, smart, quippy, beautiful, and royal, thrown in with a ragged band of misfits and swept up in adventures that got her dirty and wounded. When the men around her whined and moaned, she was undaunted. I thought this undauntedness was absolutely wonderful.

I re-read the Prydain books many times, over the years. When I was fourteen, I thought, “She’s the only one of the companions who’s female: of course she’s beautiful and smart and young. Of course she had to end up with the handsome young man, who of course turned out to be a king. Also: she stamps her foot a lot. And her eyes do a great deal of flashing.”

But analysis and cynicism always passed, as I read and re-read. These were my friends. The longing to slip into their world with them has always been there—even now, flipping through pages (when the longing is, of course, thickened with a healthy dollop of nostalgia).

How does she compare to the female characters in your work? Is she their literary ancestor? Do they rebel against all she stands for? What might your heroines owe her?

Not a single one of my female characters is like Eilonwy, because my worlds are nothing like Prydain—none of my published worlds, anyway. I did write a book when I was seventeen that featured a bunch of high fantasy tropes, and a young woman with red-gold hair, whose name was Aelwen.

That’s as close as I got. (It was, admittedly, pretty close.) I went out of my way to avoid tropes, in my later writing. Though there are a queen and a princess in my second book, the former is psychopathic, and the latter falls in love with an enemy captive and dies tragically, setting in motion a string of hideous events. Come to think of it, a queen and princess also feature in The Pattern Scars—but there’s absolutely no quippy undauntedness about them. (The princess never even learns to walk, let alone quip. Plus, she’s blind.) Aaand, as it happens, my Cretan books, The Door in the Mountain and The Flame in the Maze are centred around a deeply unlikeable princess who twists everything she sets her twisted mind to. The royalty thing does seem to have stuck.

Beyond that, though: no Prydain.

Eilonwy was the person I wished I could be when I was seven, and certain that magic had to be real. My own female characters are the people who intrigue me, now that I know it isn’t.

_______

When not working on her own books (which, sadly, is most of the time), Caitlin Sweet is a writer at the Ontario Government, and a genre writing workshop instructor at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies. She lives in Toronto with her family, which includes a science fiction-writing husband, two teenagers, four cats, a hamster, a bunch of fish, and a passel of itinerant raccoons.

If this interview leaves you hungry for more about Caitlin Sweet, check out this post by Peter Watts, here, about the Sunburst nod.

_______

About this post: The Heroine Question is my name for a series of short interviews with female writers about their favorite characters and literary influences. The link will take you to the other interviews, with awesome people like Martha Wells, Jane Lindskold, and Gemma Files.

Also about this post: A friend has recently asked about my use of the gendered word, heroine, in this series. I could have gone with hero, true, or female heroes. To be honest, my initial inspiration came from a desire to make puns: Gemma Files on Heroin! Oops! That kind of thing. I hope to get up a post that takes the answer further than “I pun, therefore I am.” And I have folded a question about this word into the later interviews; you’ll see other writers talking about it, too, in a few weeks’ time.

One of the things that went live while I was away at Readercon was an interview with me, Kelly, David Nickle and Madeline Ashby on the Speculating Canada podcast. The theme of the interview was writer couples. Derek Newman-Stille is a great interviewer, and I think I can safely speak for us all when I say we had a lot of fun talking to him.

One of the things that went live while I was away at Readercon was an interview with me, Kelly, David Nickle and Madeline Ashby on the Speculating Canada podcast. The theme of the interview was writer couples. Derek Newman-Stille is a great interviewer, and I think I can safely speak for us all when I say we had a lot of fun talking to him.