I know and admire Elizabeth Bear‘s writing–I had the good fortune to review Hammered when it was first released, and rave about Carnival

, every chance I get. I teach her story “Two Dreams on Trains” in my Writing the Fantastic course at UCLA.

I forget, sometimes, that she and I have never met. I follow her Twitter feed and her blog, where she talks about her passions, writing craft, and the artistic life with its constant juggles and challenges. It all comes across as real and familiar; it resonates with me. I feel as though I know her Giant Ridiculous Dog and cats, though in fact I don’t. I’m one of the many readers who never misses her Criminal Minds recaps, which are charmingly filed under the Geeks with Guns tag.

Even though she is an unselfish and honest blogger, I asked her to do a Journey interview out of sheer greed, just so I and you could get to know her a bit better.

PHOTO BY S. SHIPMAN

Here’s what she told me:

I live in Manchester, Connecticut, with a giant ridiculous dog, a presumptuous cat, a room-mate, and the roomie’s cat, a giant fluffy monster. I love to cook, and do it recreationally; I am an apprentice gardener and a really lousy guitar player; and I have a collection of outdoor hobbies including kayaking, rock climbing, and hiking. I read compulsively, and I’m a third-generation SF fan on both sides of the family.

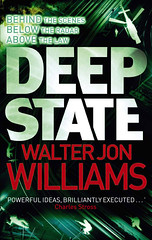

I tend to have a lot of irons in the fire in terms of projects. There’s Shadow Unit, of course–tons of free online fiction in a semi-interactive, semi real-time narrative, written by some of SFF’s best writers, established and new. I’m fortunate to be doing a lot of teaching this year–Clarion, Viable Paradise, and I’m a guest lecturer at Odyssey this fall. And I have three books coming out this month (two of them delayed from last year): The White City, a vampire novella set in an alternate Moscow around the turn of the 20th century; The Sea Thy Mistress

, a periapocalyptic Norse technofantasy, the third in the Edda of Burdens trilogy; and Grail

, far-future science fiction about posthuman explorers aboard a generation ship, the third in the Jacob’s Ladder trilogy.

I also just delivered Range of Ghosts, which is the first in a new epic fantasy trilogy I’m very excited about. It’s nearly unique, I think, in that its setting is Eurasian and Central Asian rather than European. It’s not a historical fantasy, however, but an attempt to create a fantasy setting that draws from different backgrounds than most Western fantasy.

I’ve spent a good deal of my life trying to find a real profession, something that might lead to financial stability and regular access to healthcare, but storytelling seems to be the only thing I’m any good at.

I’ve been writing fiction since I figured out that stories came from somewhere. Which is pretty much first grade, as far as I recall. I remember writing little stapled “books” of stories about dinosaurs and race horses and aliens. Apparently, this is the thing I was meant to do.

Oh, I have quit. And I have worked at various other jobs from the time I was sixteen until I was thirty-six, more or less. Some of them didn’t leave a lot of time for writing. I made a couple of fairly serious attempts to get published in the 90’s, but I didn’t have a mechanism for improving my work, at that point, and I didn’t know how to learn the necessary skills to become a professional writer, so eventually I would get frustrated and pack it in.

From 1997-2001 I basically didn’t write anything. Toward the end of that I was employed at a job that demanded sixty or seventy hours a week and didn’t pay a living wage, and I had a fairly miserable marriage. I actually got back into writing after 9/11, when I was laid off and there was no work to be had, and I had taken the dogs to the dog park so much they were becoming territorial about it. Fortuitously, at that point in time, my friend Julia Frizzell told me about an online community–the Online Writing Workshop for Science Fiction and Fantasy, where I am now, in a moment of narrative circularity, employed as a resident editor–and I was fortunate enough to fall in with a group of other writers of similar skill level who were very smart about publishing and very determined to get published.

You will recognize some of their names. Among that group was Karin Lowachee, C.C.Finlay, Sarah Prineas, Benjamin Rosenbaum, Amanda Downum, Leah Bobet–and many more, some already established, some still in the process of breaking in.

We bootstrapped each other, I think. Peer group is so amazingly important.

I’ve always been an SFF reader. I was raised to be one. I read other things too–literary fiction, mystery, biography, nonfiction, poetry.

But–other than the juvenile stage, where I wrote horse stories, and a plot-coupon epic fantasy I’m still stealing bits from (Kasimir, the steampunk warsteed in the Edda of Burdens, came from that originally, as did Gavin the Cyber-Basilisk, who appears in the Jacob’s Ladder books) –I originally started off as a poet. Because I couldn’t figure out how to write narrative arc. I had a gifted-and-talented program teacher in third and fourth grade (Mrs. Katz) and a fifth-grade teacher (Mrs. Kology) both of whom really encouraged my poetry–as did my mother, Karen Westerholm, who is an award-winning poet in her own right. She’s been a National Poetry Slam finalist.

So I wrote poetry through high school and into college, and had a lot of false starts on stories that never went beyond four pages. In college, I worked for the school paper as a journalist, which is a little more impressive than it sounds: The Daily Campus is (or was) an independently-funded paper that published five times weekly, and did a fair amount of reasonably serious reporting.

Then sometime in my mid twenties I learned how to write narratives, kind of. I have a very inductive, nonlinear thought process, and early attempts reflect that. Which is one reason I was unsuccessful in selling them. I could no longer write poetry, though.

Around 2002, I started writing work that sold, and in the last couple of years I’ve started being able to write poetry again, which is a relief.

I’ve got an unpublished YA historical mystery with Sarah Monette that we’ve been unable to sell so far. I have some ideas for more mainstream stuff I may write someday, but I’ll need to have the time to do it.

I think one writes stuff better when one has done it one’s self. I read everything I can get my hands on, talk to experts, where practicable try it myself. I am an archer; I’ve done some swordfighting; I try to keep learning new things and practice things my characters need to know.

I support myself with my writing, and sometimes (often) it’s pretty precarious. Especially with the industry in the state it’s in during the current zombie apocalypse, as Sarah Monette likes to call our Current Troubles. I write fiction, book reviews–anything that they’ll pay me for and I can find time to do. I work almost constantly, honestly, and at best I scrape by.

I so far have only taught at workshops, although I have my eyes peeled for a teaching gig–but since I don’t have a degree, and I have neither the time nor the money nor the interest in an MLA, I have to take what I can get.

Most of my money comes from fiction, though. I keep hoping the foreign rights sales will take off, but they haven’t, yet.

I work almost every day, and sometimes I put in twelve-hour days. Of course, I can do that on the couch, in my pajamas, so it’s not as onerous as it sounds. But I have to make time to schedule stuff like social time and exercise. I neglected that for a while, and it was very very bad for me.

Someday I’d like to write a Great Book, even if I’m the only one who knows it. I think the Stratford Man duology–Ink & Steel and Hell & Earth–is as close as I have gotten so far. I’d kind of like to write a graphic novel–Blood and Iron started off as one, actually, when I was in high school. And then this Matt Wagner guy came along with a little book called MAGE….

I sold some poetry to young-artist venues in fifth grade or so, and a few short stories to small markets in the 90s. But honestly, I sent my first short story to Asimov’s when it was still IASFM–and I was in high school–and I didn’t sell a story there until after I had won the Campbell. I tell people it took me thirty years of fairly consistent practice to learn to write fiction, and that’s not far off.

I don’t think in terms of sacrifices or rewards. Storytelling is my life’s work.

Awards are lovely, and they can give readers a reason to give you a chance. But honestly, I’m not a big seller. I’ve had a great deal of critical success, but I’m still very much a niche writer in terms of market. Possibly I’m just not that commercial, for one reason or another.

I could never afford something like Clarion. I’m from a working-class family, and I’ve spent my entire life living hand-to-mouth, more or less. I’ve learned to do what I do through consistent effort, the generous criticism and mentorship of my peers, and trial and error. Reading slush and critiquing the manuscripts of others has been a great teacher for me–it’s a wonderful way to see what works and what doesn’t. Sometimes polished stories are hard to pick apart to see what makes them tick.

Writing for a living is exactly what everybody says it is–a ton of work, a profoundly difficult skill it can take a lifetime to master, very satisfying and frustrating in equal measures, and a lousy way to get rich.

I mean there’s little stuff–I tell friends who are waiting for the publication of their first novel that the best thing they can do for the two months surrounding the drop date is get drunk, stay drunk, unplug the internet, and write the next book. Of course, nobody does.

Most of what happens in a book’s or a story’s career is outside of a writer’s hands. All we can do is write the best, most honest, most real things we can. And then accept that some people will love them, and some will hate them, and the vast majority will go “meh.”

Being a writer is an exercise in relinquishing control.

I often feel like I’m doing what I have to do, and doing my best to do it honestly, and help as many other people as I can. Oh, and scary. Constantly terrifying, because I am always hard up against the edge of my skill and sure I’m going to fail, or starve, or both. The first of that is the best I can ask from life; the last is a little Live! Without A Net!

Someday I’d like to feel secure, I guess. That would be nice.