I wrote a post here, called X-Men: Days of Boresville.

I wrote a post here, called X-Men: Days of Boresville.

This part of the sample critique I was writing was going to be all about how you don’t do it… how you say unkind things and mock the story. So! The snark demo seems to be covered in the pre-existing post.

Wow, I hated this film. It made me so angry. The central problem I had with the story, the part that offended all of my sensibilities, was that the past-tense storyline played out in 1973, during the U.S. military action in Vietnam. There were scenes set in a number of interesting Vietnam-related situations, including the Paris peace talks.

How cool, right? You could do a million things with that!

Part of the point was to show how the military industrial complex is always looking for their next big villain, the next reason why billions of dollars have to be spent on bigger and shinier weapons instead of, you know, food or bandaids. It’s Germans! No, it’s Communists! Brown Commies! Wait, it’s mutants! OMG!

So far, so good. The possibilities for exploiting this historical period, of creating a mutant-flavored alternate history of the Vietnam War are incredible. It wouldn’t have been off-topic, or separate from the point–we’re talking about a movie that already made the time and space to use this material. But instead, 1973 and its events were set dressing. Meaningful use of the historical subject matter verged on zero.

As a single example, let’s talk about the way Charles is taking drugs that mess with his telepathy so he can walk. The so-called serum is pitched as medication, but there’s also this ongoing cinematic dance, within the direction, that has Charles looking more than a little like an addict. They don’t have the guts to actually make him one, though.

Do I want junkie Charles? Not necessarily. Addicts and their stories are not my favorite thing. But if I’m going to have to watch him inject himself and act all withdrawaly anyway, why not take the opportunity to do some bravura characterization on this so-beloved character?

Consider: you have a teacher whose whole life is about saving mutants from their own powers and from societal discrimination. Now his school is in ruins because his students are being drafted and sent to Asia. But Charles is gleefully shooting chemicals into his arm not because he cannot bear that terrible reality. And not even because he’s a telepath, and if he keeps his powers he might feel those kids he’s linked to as they kill and die and experience unimaginable horrors. Good heavens, no!

He’s taking the serum because he doesn’t like being in a wheelchair.

Now being shot and paralyzed is a traumatic thing, I’ll grant you. And I understand that Charles isn’t meant to be all grown up and stable yet. But what’s stronger? Taking the opportunity to imagine how a compassionate and caring guy like Xavier would be affected by a war that would inevitably use his people more and harder than ordinary folks? Or being asked to care because he has to choose between superpowers and walking?

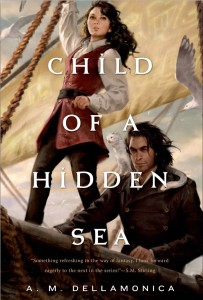

This year’s reading. If I finished it, it was at least good. If it has an asterisk after it, it was great.

This year’s reading. If I finished it, it was at least good. If it has an asterisk after it, it was great.