In the Eighties when ![]() Kelly and I were newly together, we took turns reading each other some of our favorite novels. I remember reading her To Kill a Mockingbird, sotto voce, on an Edmonton Transit bus route.

Kelly and I were newly together, we took turns reading each other some of our favorite novels. I remember reading her To Kill a Mockingbird, sotto voce, on an Edmonton Transit bus route.

The first thing she read to me was Lincoln’s Dreams, by Connie Willis.

In those days I was working a night shift at a smoke-infested rathole that called itself an answering service, 11pm to 7am, and Kelly was at the U of A finishing her degree during the daylight hours, and we were seeing almost nothing of each other. Eating and wholesome newlywed sports activities were taking up much of the rest. But we got to the reading pretty regularly, and I was enjoying the book very much. And then one night, the impact of the novel just hit me. We were about three-quarters of the way in and things had started to take a turn for the dire. I called her up from the answering service, got her out of bed and said “I have to know how it ends.”

So she read it. For hours. On the phone. In the dead of night. With interruptions when oil rig guys called in or the 24-hour lawyer got the beep to go hand-hold some drunk driver through his breathalyzer test or someone’s burglar alarm went off and I had to send the cops. Kelly got hoarse, and then as things got sadder she got hoarser, and I was answering the phones with a catch in my voice. And then it was over, and K got to go bed, and I spent the night feeling hammered… in a good way.

It’s Connie’s first book, it’s one of my favorites, and she’s only gotten better at storytelling since then. If you want to see how it begins, I’ve posted its opener here.

Anyway. I could go on. I could tell you about the fabulousness of “Blued Moon,” which K also read me, or the gut-punch amazingness of “Fire Watch.” I could tell you about the hilarious antics the first time we met her at a con… and I will tell you that one, sometime in the not too distant. But this is a great interview, and I think we ought to get to it. So, with no further “Ado” (couldn’t resist) I give you Connie Willis:

Writers live essentially boring lives. If they lived exciting lives, they’d never get any writing done. I spend a lot of time at Starbucks and/or Margie’s Java Joint, and at the library, and my exciting project for the summer is cleaning out my basement, a job akin to cleaning out the Augean Stables. (People always laugh when I say this, but they have not seen my basement. I’ve been working on it for two months with no end in sight.)

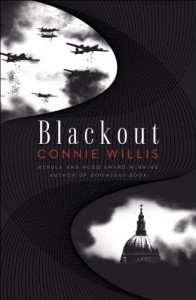

The reason it’s such a mess and why the closets all need cleaning and the yard’s a disaster is that for the last eight years I’ve been working on a novel about time travel to World War II, which started out as one volume and then became three and then got squashed back to two–Blackout and All Clear. It is NOT a duology or whatever you call it. It’s one novel, and writing it just about killed me.

I am currently in recovery, working on assorted short stories, researching a comic novel about Roswell and UFOs, and reading all the books I didn’t have time to read before, like Jerome K. Jerome‘s Tales of an Idler and A Glastonbury Romance and Raintree Country, which I’m rereading. (It should always be read in the summer.)

Blackout-All Clear is about three Oxford time travelers who are researching different civilian parts of World War II in England–the rescue of the soldiers in Dunkirk by an armada of “little boats” manned by fishermen and retired sailors; the London Blitz; and the evacuated children, when things go spectacularly wrong for them and possibly for every other historian scattered across history.

I’ve been in love with World War II ever since my eighth-grade teacher read us Rumer Godden’s An Episode of Sparrows, about a little girl who makes a garden in the rubble of a church bombed out during the Blitz. I wrote about it in “”Fire Watch” and “Jack” and “The Winds of Marble Arch”, but I wanted to write about it in depth, particularly about the civilian contributions to the war, which most people don’t know about.

One of my favorite stories about the Blitz is about an old woman pulled from the rubble. Thinking there might be others buried there with her, the rescue squad asked her, “Is your husband in there with you?”

“No,” she said, “the bloody coward’s at the front.”

I wanted to tell the stories of all those shopgirls, parlormaids, retired sailors, church ladies, mathematicians, and children who found themselves unexpectedly at the front–and essential to a war that couldn’t be won without them.

I can’t remember when I began writing stories, but I spent a good chunk of my childhood playing with my dolls and making up stories, swinging and making up stories, lying in the grass and making up stories, lying in bed and making up stor–well, you get the idea.

In sixth grade I was given a copy of Little Women, at which point I not only knew I wanted to be a writer, but which writer: Jo March, who sat in the garret with ink all over her fingers and scribbled and tied her manuscripts up with pink ribbon. After that there were Anne of Green Gables (also a writer) and Betsy of the Betsy-Tacy books (ditto), and I was headed toward a life of writing girls’ books when I picked up Have Space Suit, Will Travel and discovered the Wonderful World of Science Fiction.

Heinlein was of course my first love (he was my entire science-fiction generation’s first love), but it was the short stories I fell in love with. My library had all the Year’s Best collections, the ones edited by Judith Merril and Anthony Boucher and Robert P. Mills, and I read them from cover to cover–stories by Kit Reed and Fredric Brown and Philip K. Dick and Zenna Henderson and Ray Bradbury, “The Star” and “It’s a Good Life” and “The Cold Equations” and “Flowers for Algernon” and “One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts.” It was there that I got my first glimpse of how amazingly diverse and expansive the field was and of how many different types of stories and voices and styles there were and how many possibilities. I became convinced I could tell almost any kind of story I needed to in either science fiction or fantasy, and after all these years, I still feel that way. A field that can produce “A Little Something for Us Tempunauts” and “Lot” and “Bernie the Faust” and “The Cloud Sculptors of Coral D” is clearly a place where anything is possible.

By the time I graduated from high school, I knew I wanted to be a professional writer, though it never occurred to me I’d be able to make a living at it. My plan was to teach and write in the summers and on spring and Christmas breaks, a la Zenna Henderson. So I majored in elementary education at college, with an English major on the side (so I’d have an excuse to read lots of books), then got married, taught (and wrote) for two years, and then got pregnant, at which point I decided to stay at home with the baby and try to write full-time.

(Throughout all of this–and my entire career–I’ve had the support of my wonderful husband, for which I am very grateful. I never had the pressures so many of my writing friends have had of having to bring in that regular paycheck. As a result, I’ve been able to keep writing short stories, which I love, and to take years and years to finish my novels. (Doomsday Book took five, and Blackout-All Clear took eight.)

I’m lucky enough to be able to write full-time, which actually means I write when I’m not giving speeches, going to conventions, doing research, teaching writing workshops, talking to libraries and book clubs and assorted other groups, or writing introductions and blurbs for other writers. I occasionally manage to squeeze in a little real writing in there, and it’s better than trying to juggle writing with another job.

It wasn’t always this way. I subbed for a long time when I was getting started, worked for a nursery school, and ran a nursery school of my own. I was constantly frustrated because I couldn’t find the time to write, and I still am.

One thing I learned back in those subbing/teaching days was to take advantage of every free second. I had heard some writer say that unless you wrote for at least three hours straight, it wasn’t worth even sitting down. I remember thinking, “Oh, my God, I’ll be eighty before I have a three-hour stretch.”

So I started carrying a notebook everywhere and writing whenever I had a few minutes: in the orthodontist’s waiting room, on the bleachers, in line at the post office. Ten or fifteen minutes isn’t long enough to write a story or even a scene, but it is long enough to do a paragraph of description or a conversation or a transition, or to jot down some notes about the plot.

To do this, you have to be ready to write, and whenever I was walking somewhere or doing dishes or driving a long distance, I’d think out the dialogue or scenes I was going to write the next time I had the chance.

I’d write my stories in dozens of little fifteen-minute pieces till I had enough to justify grabbing a whole afternoon to put them all together. I wrote “A Letter from the Clearys” and “Samaritan” and “Fire Watch” that way, and it’s a technique I still use.

I sold the first thing I ever sent out (an article in The Grade Teacher) and one of the first stories I submitted (a mainstream story to Ingenue called “The Villains of the Piece”), and two years later I sold my first science-fiction story, “Santa Titicaca”, to Worlds of If, which promptly went belly up. But it was nearly eight years before I began selling with any consistency, and during that period there were lots of discouraging moments and lots of rejection slips.

The one I particularly remember was the day I found a pink slip in my mailbox and, thinking it was a present from my grandmother, took it blithely up to the counter.

It wasn’t a present–it was the rejected manuscript of every single story I had out, I think eight stories in all. Always before when I got a rejection slip, I had been able to tell myself that that one hadn’t sold, but they were sure to buy this other story I had out. This time, there was no way I could do that. They’d rejected everything, and it seemed to me that somebody was trying to tell me something, and that this would be a really good time to give up.

Even worse than the rejection slips (and I don’t care what anyone says, it’s impossible not to take them personally), was the disapproval of friends and extended family (my immediate family has always been great) and their feeling that I was wasting my time and should get a “real” job. Best of all was the conversation that went like this:

“And what do you do?”

“I’m a writer.”

“Oh. Have you ever sold anything?”

I finally got so sick of having to say “no” (and of worrying about not contributing anything financially–one of our neighbors actually said, “How does your husband feel about your mooching off him like that?”) that I started writing stories for the confessions magazines. You know, like True Romance and Secrets and True Confessions. They not only paid good money and enabled me to say “Yes,” when people asked me if I’d ever sold anything, but they were fun to write, and they were a great place to practice all the techniques I needed to learn: dialogue, flashbacks, story arcs, character, and setting.

But what I really wanted to write (and did write–the stories just weren’t selling) was science fiction. I think it’s really true that every author has to write a hundred thousand words of junk before they get to be any good, and I spent those eight years doing just that, from confessions like, “While My Husband Took the Kids to Church, We Prayed We Wouldn’t Get Caught” to a modern Gothic novel (also never sold) to lots of science fiction stories.

It wasn’t all grim, though. I was paying the insurance payment and the gas bill with “I Called for Help on My CB–And Got a Rapist Instead!” and “A Boyfriend for Grandma”, my grandmother loved what I was writing, and in 1976, I was put in touch with Ed Bryant’s writing workshop and found a group of kindred spirits–Cynthia Felice, Pete Alterman, John Stith, and Ed Bryant. They introduced me to the wonderful world of science fiction conventions, to dozens of other authors, and to the week-long Milford writing conferences, which Ed was running then at various places in the Colorado mountains, and at which I met wonderful writers like Carol Emshwiller, David Gerrold, Dave Skal, and George R.R. Martin.

I never went to Clarion. Those Milfords and the Southern Colorado Workshop were my Clarion, and they changed everything for me. They connected me to what was going on in the field, corrected all my horrible writing mistakes–“Your narrator sounds just like Shirley Temple,” Ed told me during one of my first critiques–and best, of all, didn’t think there was anything peculiar about my wanting to be a professional writer. Every writer needs a group like that, whether it’s Clarion or a local workshop or one you belong to on-line. Writing is a solo business, but being a writer isn’t, and it’s almost impossible to keep going on your own through the discouraging and self-doubting times. (Which I still have. During the last few months of writing Blackout-All Clear, when I was convinced I was never going to finish it, and when I did finish it, it was going to be dreck, I was on the phone to those same people I met during those early years. They’re your comrades in arms, the band of brothers you’ve got to have to survive as a writer.)

My advice for being a writer is simple. Don’t give up, even if all eight of your manuscripts come back on the same day and all your friends are saying you should get a job. Every writer has these moments–Faulkner painted his whole den with rejection slips, Frank Herbert wrote four unnoticed novels before Dune, Harrison Ford worked as a carpenter for ten years before becoming Han Solo. Anything worth doing is worth going through a little anguish for.

My advice for the writing itself? Write what you want to, not what’s currently hot or what you think will be the Next Big Thing. That never works, and besides, if you became a writer because you wanted to become rich and famous, you should have picked another career. Writing is far too difficult to do it for any reason other than that you love it. My favorite thing in the world is writing romantic comedies. They didn’t exist either in science fiction or in the confessions magazines, but I wrote them anyway, and they were the first things that sold, mostly because I had such a good time writing them.

But I would also have written them even if nobody had ever bought them, and that’s the key.

Write what you love. Period.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Journey – with Connie Willis | A.M. Dellamonica -- Topsy.com