Kelly Robson attended the utterly awesome Taos Toolbox master class in 2007, and has two stories coming out next year, in Start a Revolution and The Exile Book of New Canadian Noir. She was tagged by Caitlin Sweet to do the Writer’s Process blog meme (as was I) and, as she’s not maintaining a blog of her own these days, it was suggested that she might post her answers here. What a brilliant idea!

Kelly Robson attended the utterly awesome Taos Toolbox master class in 2007, and has two stories coming out next year, in Start a Revolution and The Exile Book of New Canadian Noir. She was tagged by Caitlin Sweet to do the Writer’s Process blog meme (as was I) and, as she’s not maintaining a blog of her own these days, it was suggested that she might post her answers here. What a brilliant idea!

Kelly can be found online at Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest. Here’s what she has to say:

I started the first draft of this Process Blog Tour post by waffling over whether I have enough real writer points to legitimately respond. But screw that. Cut cut cut. Then I delayed posting this because I felt superstitious — like if I posted it I’d never write fiction again. Dumb, hmm? But Caitlin Sweet tagged me because she’s interested in what I have to say, so let’s just do this. Protesting too much is boring. Delay is boring.

What am I working on?

Final revisions on a historical horror story set in 19th century Bavaria. Horror isn’t my thing at all, but I wanted to submit something to a particular anthology so I waded in. When I first started drafting, I got myself quite freaked out while conjuring the horrific elements (I have an overactive imagination). It’s okay now, though.

I was surprised to discover that horror seems to require huge amounts of sensory information, and I loved writing that. It was an excuse to get a little lyrical, where otherwise my writing tends to be quite straightforward.

On the novel side of things, two potential projects are battling for supremacy. One is an alternate-present fantasy and the other is near-future non-genre. Both have their pros and cons. I just need to decide which project will make me happiest — which pinata contains the most candy.

How does my work differ from others in its genre?

God, what a loaded question. First of all, I reject genres as anything other than marketing categories. Some people only read within certain marketing categories and that’s great if it works for them. I read the best (as I define it) across all categories. That goes for all media.

So I’ll redefine the question to: What characteristics does my work have that I think might be somewhat unusual?

I’m not interested in writing about characters like myself. To date I’ve mostly pursued male characters. Out of the three stories finished this earlier this year, one MC is a mentally disabled Viennese janitor, one is a potty-mouthed Australian winemaker, and one is an Enlightenment-era French slut. All men.

Maybe that’s because I’m mostly interested in characters who are absolutely convinced by the actions they’re taking and it’s easier to imagine men moving through the world with that kind of conviction. Women tend to be more ambivalent unless they’re pretty extreme outliers. But I’m not interested in extreme outliers.

However, the new historical horror has a lesbian MC. She’s backed into a corner physically, financially, and emotionally, so I hope she’s moving with conviction. I had trouble getting her there, and I’m afraid she might not be sympathetic enough.

Why do I write what I do?

Better to ask why I write at all. Because it would be better if I didn’t. All writers know that the opportunity cost for what they do is huge and the chance of it ever paying off financially is little to none.

I write because I’ve always wanted to — always — and getting the psychological permission to do it was one fuck of a battle that only started turning when I approached 40.

I write because it’s taken over 300,000 words to figure out how to write something I’m proud of. I’ve got great taste, and I can tell when something’s shit even if I’ve shat it out myself. So after learning how to please myself it would be a damn stupid waste to stop now.

I write because it’s mentally beneficial and controls my anxiety. Which is a way of saying that I really NEED to.

I write because finishing something and having people you respect like it, understand it, maybe even love it, is the best feeling in the world.

I write because many of the people I love and respect are writers, and I always felt like an outsider when I visited their playground. That wasn’t a good feeling. It also wasn’t a good way to achieve the recommended levels of mental health and self-love.

I write because I love fiction and can’t live without it, but I don’t love it unconditionally. I have high and exact expectations that are rarely met. So if I want to read something that pushes all my buttons, I have to try to write it myself.

How does my writing process work?

Output

I’ve tried the “quantity not quality” thing and it doesn’t work for me (it was a great way to learn though). It just makes a mess too awful to face cleaning up. Not very many people can write quickly and produce something worth reading. I think the quantity not quality orthodoxy is responsible for a lot of crap.

Some people can write a story in a weekend. That’s not me. For the previous two stories, seems like I’ve gotten a 5000 word draft in a month by working at least eight hours a week. Then finishing it takes huge amounts of revision — 30-40 hours. Maybe 100 hours per story total. I haven’t actually calculated it.

Process

I start a drafting session by grooming the last 1000 words or so to make sure I’m not headed off on a tangent. That means by the time I have a complete first draft it’s already been revised at least three times, except for the end. Which means the ending sucks. Then I rewrite several times before asking Alyx to weigh in on it. She’s wonderful at critique not only because she’s a terrific writer and experienced critiquer, but she also teaches writing so is very smooth at communicating her opinions and fixes. Rewrite again and get another crit from a friend. Then rewrite again and again. Maybe 5-10 revisions?

Revise, revise, revise. There is no other way.

Tools

My most unusual tool is an 11 x 14 inch sketchpad, which I use to doodle scene mechanics, story, and plot. If I’m spinning my wheels, the sketchpad will usually put me on track again. Scribbling has always helped me think.

Location

Our condo is too small for me to have a desk. My laptop lives in a drawer. But our condo building has a library with wifi, which is nice. Our kitchen table works too. Often Alyx and I will write in a coffee shop. The current spot is Jimmy’s on Gerrard, which has two upper floors with big tables.

I can draft on an iPad with a regular Mac bluetooth keyboard, which is great to haul around to the coffee shop. This setup is no good for revision because cutting and pasting and flying around a document with efficiency is impossible on an iPad.

Research and inspiration

I read a lot of non-fiction. Good, clear non-fiction primes my brain for the kind of writing I want to achieve. I actually think that Alan Bennett’s essay collections Writing Home and Untold Stories

and Untold Stories are magical in this way. I can’t recommend them highly enough.

are magical in this way. I can’t recommend them highly enough.

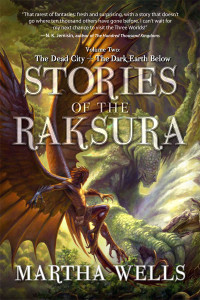

A (barely) belated Happy Book Birthday to Martha Wells, whose Stories of the Raksura: Volume Two

A (barely) belated Happy Book Birthday to Martha Wells, whose Stories of the Raksura: Volume Two came out yesterday! Martha has written over a dozen fantasy novels, and this particular series, Books of the Raksura, includes The Cloud Roads, The Serpent Sea, The Siren Depths, and Stories of the Raksura Vo.l I as well as this new volume.

It would be pretty easy to imagine my own kids rebelling against my love of reading, which my wife shares. “Dad’s an author? Great. Hand me the remote.” But early on they discovered the same thing I did: Books are treasure boxes; they just beg to be opened. Their favorites have been the Magic Tree House and the Magic School Bus, Harry Potter and most recently the Hunger Games books. To be honest, I don’t care what titles they’re drawn to — as long as they’re reading, I’m happy. Sounds like something my Mom and Dad would have said.

It would be pretty easy to imagine my own kids rebelling against my love of reading, which my wife shares. “Dad’s an author? Great. Hand me the remote.” But early on they discovered the same thing I did: Books are treasure boxes; they just beg to be opened. Their favorites have been the Magic Tree House and the Magic School Bus, Harry Potter and most recently the Hunger Games books. To be honest, I don’t care what titles they’re drawn to — as long as they’re reading, I’m happy. Sounds like something my Mom and Dad would have said.