Guesting today on the site is D.B. Jackson, also known as David B. Coe, the award-winning author of more than a dozen fantasy novels. His first two books as D.B. Jackson, the Revolutionary War era urban fantasies, Thieftaker and Thieves’ Quarry

and Thieves’ Quarry , volumes I and II of the Thieftaker Chronicles, are both available from Tor Books in hardcover and paperback. The third volume, A Plunder of Souls

, volumes I and II of the Thieftaker Chronicles, are both available from Tor Books in hardcover and paperback. The third volume, A Plunder of Souls , has recently been released in hardcover. The fourth Thieftaker novel, Dead Man’s Reach, is in production and will be out in the summer of 2015. D.B. lives on the Cumberland Plateau with his wife and two teenaged daughters. They’re all smarter and prettier than he is, but they keep him around because he makes a mean vegetarian fajita. When he’s not writing he likes to hike, play guitar, and stalk the perfect image with his camera.

, has recently been released in hardcover. The fourth Thieftaker novel, Dead Man’s Reach, is in production and will be out in the summer of 2015. D.B. lives on the Cumberland Plateau with his wife and two teenaged daughters. They’re all smarter and prettier than he is, but they keep him around because he makes a mean vegetarian fajita. When he’s not writing he likes to hike, play guitar, and stalk the perfect image with his camera.

I come from a family of readers, and so, perhaps not too surprisingly, I also come from a family of writers. But the thing is, neither my father nor my mother was a writer; on the other hand all four of us kids have written professionally in some capacity, which is pretty remarkable. The common denominator for all of us was books. My parents’ house was filled with them; every shelf overflowed with paperbacks and hardcovers, novels and biographies. When I reached a certain age — maybe I was eight — my father set up my own set of bookshelves in my room, fixing brackets to the wall so that I could adjust the shelves as I needed. He had done the same thing for my three older siblings before me. It was a rite of passage in our house.

My parents instilled in all of us a reverence for the written word. They didn’t spoil us; they limited gifts of candy or toys to our birthdays and Christmas. But they were always willing to buy us books. Always. And the truth is, I’m much the same way with my kids.

I didn’t read a lot of fantasy or science fiction early on, though eventually, with the help of a camp counsellor, I stumbled upon my first novel in the genre that would dominate my adult life. And I’ll get to that in a moment. But the first reading influences I remember were pretty standard kid fare. There were a series of books that I absolutely loved titled _____ Do the Strangest Things. Birds Do the Strangest Things, Fish Do the Strangest Things, Insects Do the Strangest Things, etc. They were essentially the written, kid-friendly equivalent of a David Attenborough nature special. I couldn’t get enough of them. I read every one of them, and then read them again. And again.

Though I remain a dedicated nature enthusiast, I don’t write natural history, and so it would be easy to assume that these books had little influence on my writing career. But I believe they had a much greater impact on me than one might imagine. They fed a deeply rooted intellectual curiosity and taught me — as my parents hoped they would — that books held answers, not only to all the questions swirling around in my young brain, but also to those questions I hadn’t yet thought to ask. I don’t think it’s too great a stretch to say that these books, and others like them, started me down the path to academia, which, in turn, steered me toward my writing career.

The other books that I remember gobbling up in my youth were the Hardy Boys mysteries written under the name Franklin W. Dixon. These were the Grosset and Dunlap re-imaginings of the series published initially in 1959 and popular through the 1960s and 1970s (which is when I was reading them). They weren’t great literature, they weren’t terribly challenging as kids’ reading went. But they were enormously fun. If Birds Do the Strangest Things, satisfied my burgeoning curiosity, these books fed my craving for adventure, danger, thrills — all the things my comfortable suburban childhood lacked.

And so, by the time I went off to sleep away camp for the summer as an eleven year-old, I was primed for a new kind of book that would be both engaging and exciting enough to allow me to move on from the Hardy Boys, which I was already starting to outgrow. Enter The Hobbit.

I didn’t actually encounter the book that summer. Instead, I tried out for a dramatized version of Tolkien’s novel. I had already discovered early in the summer that I had a flair for drama (no one who knows me now will be at all surprised) and when the opportunity came to audition for this newest production, I took full advantage. Yes, I was cast as Bilbo Baggins. It helped that I was short for my age . . .

I fell in love with the story, and more I was fascinated by the world revealed to me by the script. Elves, dwarves, wizards, dragons — what was not to love. It had never occurred to me that there were books like this waiting to be read; I certainly never dreamed that there were similar books written for adults that would allow me to pursue my new-found fascination with magical stories well past my childhood. But when the summer was over, I found the novel version of The Hobbit and devoured it. Then I read The Lord of the Rings, and after that Ursula LeGuin’s EarthSea Trilogy. By then, I was hooked on fantasy, and I have been ever since.

But I think it bears repeating that I’m not an author because of Tolkien. I wrote my first “book” when I was six; writing stories was always my favorite school activity. My early experiences with fantasy didn’t set me on the road to a career as a fantasy author; the sheer act of reading had taken care of that long before. The environment created by my parents and their exuberant love of all things book were the most formative forces in my childhood.

It would be pretty easy to imagine my own kids rebelling against my love of reading, which my wife shares. “Dad’s an author? Great. Hand me the remote.” But early on they discovered the same thing I did: Books are treasure boxes; they just beg to be opened. Their favorites have been the Magic Tree House and the Magic School Bus, Harry Potter and most recently the Hunger Games books. To be honest, I don’t care what titles they’re drawn to — as long as they’re reading, I’m happy. Sounds like something my Mom and Dad would have said.

It would be pretty easy to imagine my own kids rebelling against my love of reading, which my wife shares. “Dad’s an author? Great. Hand me the remote.” But early on they discovered the same thing I did: Books are treasure boxes; they just beg to be opened. Their favorites have been the Magic Tree House and the Magic School Bus, Harry Potter and most recently the Hunger Games books. To be honest, I don’t care what titles they’re drawn to — as long as they’re reading, I’m happy. Sounds like something my Mom and Dad would have said.

David blogs, is active on Facebook and Goodreads, and Tweets. Give him some love here in comments or go forth and beard him in his lairs.

Over on Facebook, several people tagged me in the “list ten books that have stayed with you” meme. It has taken me awhile to get to it, in part because the moment I started, I realized I needed a list for childhood faves and a second one for books that had an impact since I’ve been an adult. Here’s the latter list, in no especial order:

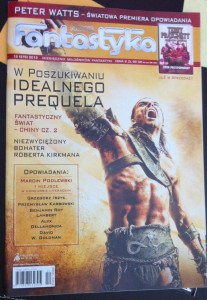

Over on Facebook, several people tagged me in the “list ten books that have stayed with you” meme. It has taken me awhile to get to it, in part because the moment I started, I realized I needed a list for childhood faves and a second one for books that had an impact since I’ve been an adult. Here’s the latter list, in no especial order:, by Connie Willis. When we were first married, Kelly and I took turns reading each other novels that were important to us. She got to the crisis in this book one evening, shortly before I had to head off to work at an all-night answering service. I phoned her as soon as things got slow and begged her to finish it over the phone. It took her until 1:00 in the morning. I started rereading it the next day.

, by Harry Turtledove. This was my first real introduction to long-form alternate history, and the first scene whereby a not-assassinated Abraham Lincoln is talking to trade unionists about their rights blew my brain right out of its skull. (I keep tchotchkes and TTC tokens there now.)

, by Peter Straub. This could just about go on the childhood list. It’s a book I’ve returned to, every couple years, since I was in my teen.

, by Neal Stephenson. Early Stephenson often makes me happier than later Stephenson, though I have mad love for Snow Crash

, too. This one, with its poisoned lobsters and anti-pollution activists, goes straight to my enviro-geek heart.

, by Minette Walters, absolutely fascinates me. I reread it just about yearly. The ending gets me every time.

, by Tana French. I’ve gone on at length about this one, and its gorgeous prose and unreliable narrator, before.

, by Nicola Griffith. And its sequels. Lesbian noir, with a point of view so convincing it makes you feel as though someone’s reached inside your brain and rewired you.

, by Walter Jon Williams, a man who has written so many brilliant novels. And yet this is the one I love: a retelling of Huck Finn as a modern U.S. disaster novel. Heart, heart, heart.

, by Jasper Fforde. An alternate world where people care about literature the way people here care about football. With time travel to boot. Oh Emm Effin’ Gee!

, by Donn Cortez. Another book whose final line just kills. This was written prior to Darkly Dreaming Dexter

, but the concept is similar. Is it darker? Less dark? You decide.

It would be pretty easy to imagine my own kids rebelling against my love of reading, which my wife shares. “Dad’s an author? Great. Hand me the remote.” But early on they discovered the same thing I did: Books are treasure boxes; they just beg to be opened. Their favorites have been the Magic Tree House and the Magic School Bus, Harry Potter and most recently the Hunger Games books. To be honest, I don’t care what titles they’re drawn to — as long as they’re reading, I’m happy. Sounds like something my Mom and Dad would have said.

It would be pretty easy to imagine my own kids rebelling against my love of reading, which my wife shares. “Dad’s an author? Great. Hand me the remote.” But early on they discovered the same thing I did: Books are treasure boxes; they just beg to be opened. Their favorites have been the Magic Tree House and the Magic School Bus, Harry Potter and most recently the Hunger Games books. To be honest, I don’t care what titles they’re drawn to — as long as they’re reading, I’m happy. Sounds like something my Mom and Dad would have said.